There can be your advertisement

300x150

"Horseshoe of Luck": Secrets of the Ginzburg House

We tell you about a real architectural masterpiece

On Novinsky Boulevard in Moscow stands an unusual building — snow-white, raised above the ground on columns, with long ribbon windows and a flat roof. Its silhouette resembles a horseshoe or a ship floating above the park's greenery. This is the famous Ginzburg House — one of the most brilliant monuments of Soviet constructivism, a building that had an enormous influence on 20th-century world architecture and inspired Le Corbusier himself. After a major restoration completed in 2020, this legendary house is experiencing a second birth, revealing its secrets to new generations.

The Dream of New Living

The story of the Ginzburg House began in the late 1920s, when the People's Commissar of Finance of the USSR Nikolai Milutin, fascinated by ideas about creating a new lifestyle for Soviet citizens, approached architect Moisei Ginzburg with an offer to design experimental housing for his staff.

Moisei Yakovlevich Ginzburg (1892–1946) was not just a talented architect but also a theorist and ideologist of constructivism, leader of the creative group OSA (Union of Contemporary Architects). In 1928, he organized a section for typification at the Construction Committee of the RSFSR, which worked on developing new types of housing. It was here that the concept of a "transitional type house" — an intermediate link between bourgeois housing of the past and communist dormitories of the future — was born.

Following these ideas, Ginzburg together with architect Ignatius Milinis and engineer Sergei Prokhorov created a project for a house that the author himself called an "experimental transitional type house." Construction took place from 1928 to 1930, and its original name has been preserved in architectural history.

Photo: pinterest.com

Photo: pinterest.comRevolutionary Structure: House as a City

The Ginzburg House was designed as a mini-city, intended to provide residents with everything needed for full life. Initially, the complex consisted of three buildings connected by walkways:

Residential Block — a six-story building on column supports with apartments of various types.

Communal Block — a two-story building with a public dining room, library, gym, and solarium on the roof.

Laundry Block — a small block with household rooms (lost during construction).

- Besides, the original project included a children's block that was never built. All buildings were connected by covered walkways, forming a unified organism where domestic functions were distributed across different zones.

This structure reflected the idea of a new socialist lifestyle: everyday tasks (cooking, laundry, childcare) were to become communal, freeing people for creative labor and self-development.

Apartment-Cells: Experiment in Action

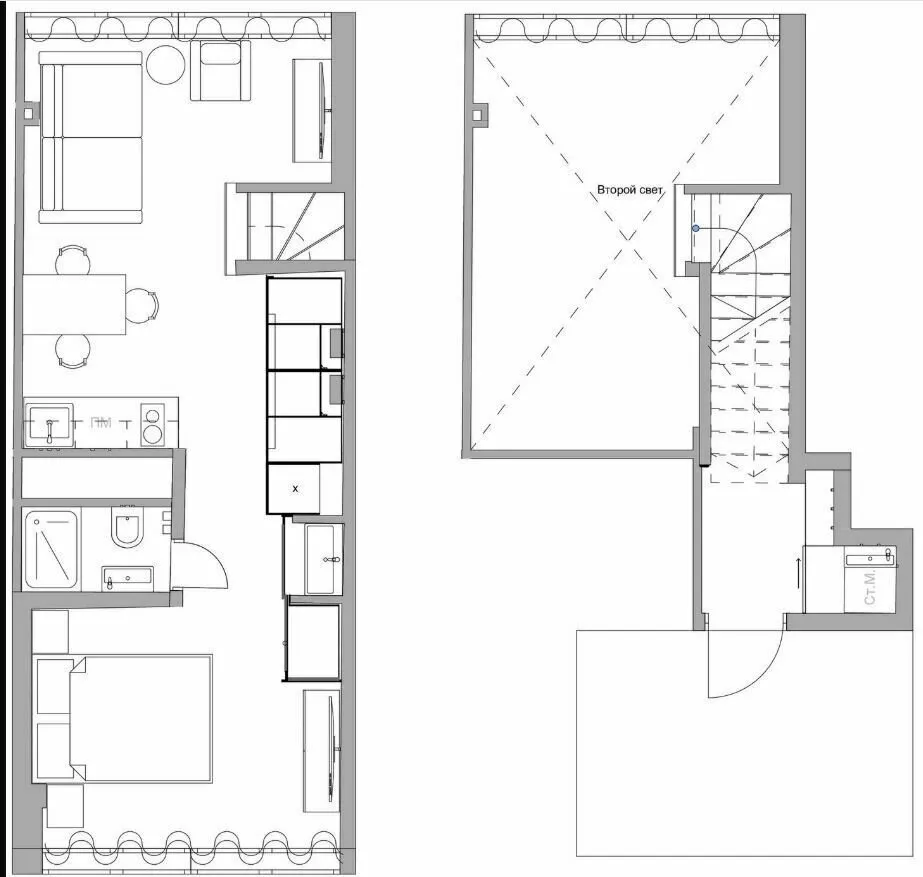

The real revolution was the internal organization of living space. Ginzburg developed six types of apartment-cells (A to F), differing in layout and size. In the Ginzburg House, mainly types F and K were implemented.

The most famous were the two-level apartment-cells of type F, where the idea of space economy was embodied through vertical division. Entering such an apartment, one would enter a small vestibule with a bathroom from which a staircase led to the main space — a living room with high ceilings (up to 3.6 meters) and large windows. The sleeping area and bathroom were arranged on a mezzanine with lower ceilings (2.3 meters).

This allowed for creating the feeling of spaciousness and air within a total area of 30–35 square meters. The “compact” auxiliary spaces were compensated for by the height and good lighting of the main living room.

Interestingly, furniture was also specially designed for these apartments — transformable, compact, and multifunctional. For example, a table could fold into a bookshelf, and a wardrobe could become a partition.

Photo: pinterest.com

Photo: pinterest.comFive Principles of Le Corbusier in the Ginzburg House

The Ginzburg House is often called a predecessor of Le Corbusier’s architecture, although historically it was somewhat more complex. Moisei Ginzburg was well familiar with the ideas of the French architect, who published his famous "Five Principles of Modern Architecture" in 1928:

Support Columns — the building rises above the ground on supports, freeing space underneath.

Flat Roof-Terrace — the roof is used as an additional functional space.

Free Layout — load-bearing walls are replaced by columns, allowing for free internal arrangement.

Ribbon Windows — horizontal windows along the entire facade ensure maximum natural lighting.

Free Façade — the façade is freed from load-bearing function and becomes light, “hanging”.

- All these principles were embodied in the Ginzburg House. The building stands on columns, has a flat roof with a solarium, its façades are pierced by horizontal ribbon windows, and the internal layout is freely organized without binding to load-bearing walls.

There is an opinion that Le Corbusier, who visited the USSR and was well familiar with Ginzburg’s works, drew much from his experience for future projects. This is especially evident in the famous "Marseilles Block" (1947–1952), where the French master used similar principles of space organization and two-level apartments.

From Obscurity to Revival

The fate of the Ginzburg House was as dramatic as its architecture. Already in the 1930s, ideas of communal living were rejected by Soviet authorities; public spaces were repurposed, and apartment-cells turned into regular communal flats. By the 1980s, the building had deteriorated into a state of emergency and was repeatedly considered for demolition or redevelopment.

In 2006, the World Monuments Fund included the Ginzburg House in its list of 100 world buildings at risk of destruction. The building’s salvation was taken up by the architect's son and grandson — Vladimir and Alexei Ginzburg. They dreamed of restoring it according to original blueprints found in the family archive.

In 2017, large-scale restoration work began under Alexei Ginzburg’s leadership. The project attracted wide attention — it was the first scientific restoration of a Soviet constructivist monument of such scale. The work concluded in 2020, and the house reopened its doors to residents and visitors.

Photo: pinterest.com

Photo: pinterest.comInteresting Facts and Secrets of the Ginzburg House

Over nearly a century, the Ginzburg House has accumulated numerous interesting facts and legends:

The First Soviet Penthouse. On the roof of the residential block, a separate mansion was built for the People's Commissar of Finance Nikolai Milutin — essentially, the first Soviet penthouse. Today this space is used as an exhibition area.

Colorful Interiors. Contrary to popular belief about the monochromatic nature of constructivism, the interiors were vividly painted. Different color schemes were used in various rooms: warm tones (ochre and lemon) in some, cool ones (blue and greenish) in others. These colors were restored during the restoration.

Experimental Materials. Innovative materials for their time were used in the building — fiberboard (pressed wood chips with a binding agent) for partitions and xylolith (a mixture of sawdust and cement) for floors.

"Living" Masterpiece. After restoration, the Ginzburg House became not a museum but a living and functioning object. It now has residential apartments, public spaces, a café, and a bookstore. Guided tours are held to see the famous apartment-cells from inside.

Global Recognition. In 2021, the restoration of the Ginzburg House was honored with a special award from an authoritative international architectural restoration competition, and the object was included in UNESCO’s Cultural Heritage List.

Photo: pinterest.com

Photo: pinterest.comLegacy of the Ginzburg House in Modern Architecture

The influence of the Ginzburg House on world architecture is hard to overestimate. Many techniques first applied by Ginzburg became classics of modernism and found reflection in the works of architects worldwide:

Two-level apartments with double-height spaces;

Compact residential cells with transformable space;

Functional zoning of housing complexes;

Use of flat roofs as public spaces;

Raising buildings on supports to free up space underneath.

Today, the Ginzburg House is not only an architectural monument but also a living laboratory demonstrating the relevance of its ideas from almost a century ago for modern urban housing. Compact apartments, multifunctional spaces, integration of living and public functions — all these solutions are once again in demand in the 21st century.

How to Visit the Ginzburg House

Tours. The Museum of Modern Art "Garage" regularly organizes tours to the Ginzburg House, including visits to residential blocks and public spaces.

Café in the Communal Block. In the restored communal block, a café is open to all. It offers an excellent view of the residential block.

Bookstore. On the first floor of the residential block, there is a bookstore specializing in literature on architecture and design.

Exhibitions and Events. The house regularly hosts exhibitions, lectures, and other cultural events related to avant-garde architecture.

Address: Moscow, Novinsky Boulevard, 25, building 1.

The Ginzburg House is not just a building — it's an entire chapter in the history of 20th-century architecture. Having survived difficult times and undergone a major restoration, it is once again relevant today, inspiring new generations of architects and designers. The "Horseshoe of Luck," as it is sometimes called due to its distinctive shape, continues to carry forward its ideas into the future, proving that true architectural masterpieces are always modern.

Cover: pinterest.com

More articles:

Urban Garden All Year Round: How to Grow Vegetables and Herbs on a Balcony

Urban Garden All Year Round: How to Grow Vegetables and Herbs on a Balcony Light of Southern Sun: How They Designed the Kitchen in a Stalin-era Apartment in Ufa

Light of Southern Sun: How They Designed the Kitchen in a Stalin-era Apartment in Ufa Minimalist and Light: How They Designed a Stylish Entrance in a Stalin-era Apartment

Minimalist and Light: How They Designed a Stylish Entrance in a Stalin-era Apartment 8 Ideas We Spotted in the Transformed Stalin-era Apartment from 1953

8 Ideas We Spotted in the Transformed Stalin-era Apartment from 1953 Sunshine Accent: How They Dared to Style a Bright Kitchen in Trash

Sunshine Accent: How They Dared to Style a Bright Kitchen in Trash Bathroom 6.9 sq.m: How Glass Blocks and Colors Created a Wow Effect

Bathroom 6.9 sq.m: How Glass Blocks and Colors Created a Wow Effect Top-6 Storage Secrets We Spotted in a Bright Trash

Top-6 Storage Secrets We Spotted in a Bright Trash Before and After: Budget Transformation of a 32 m² Studio in a Khrushchyovka Without a Designer

Before and After: Budget Transformation of a 32 m² Studio in a Khrushchyovka Without a Designer